An Undergraduate Research Project in the Humanities undertaken by Stevenson University & Maryland Humanities

Made possible by a generous grant from the Council of Independent Colleges

Benjamin Edes: Baltimore Printer and Patriot

(1784 – 1832)

The Edes Family: Grandfather, Father, and Sons

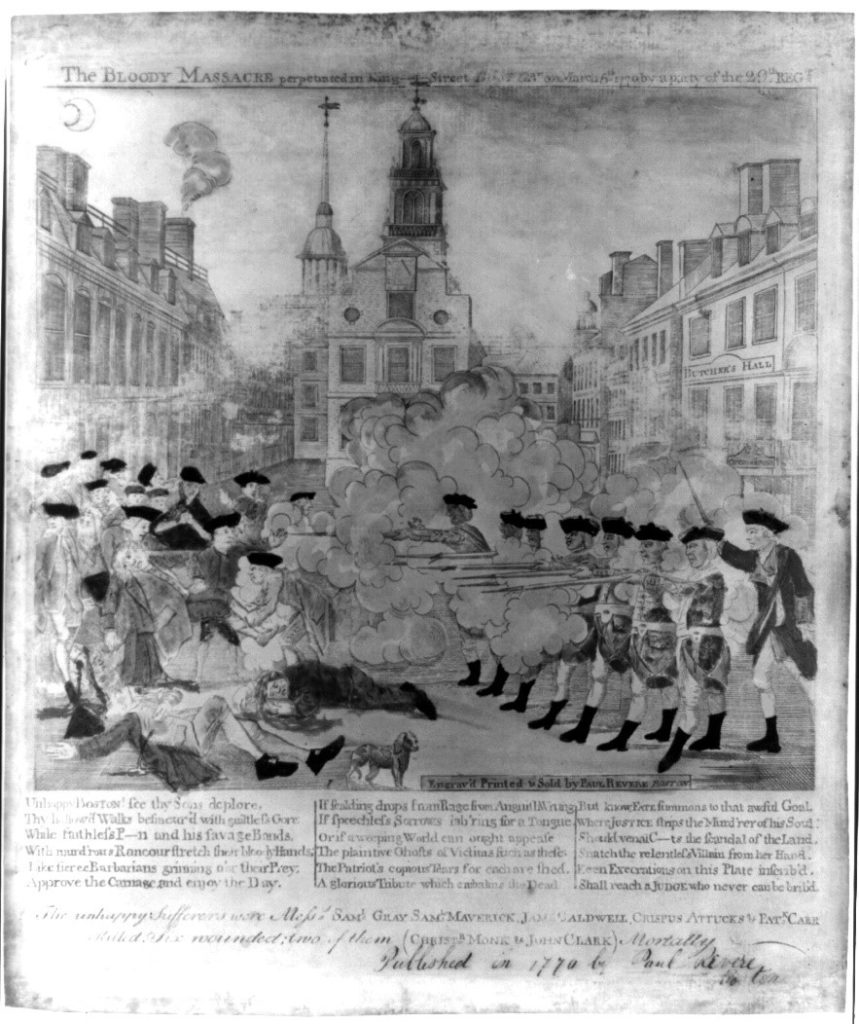

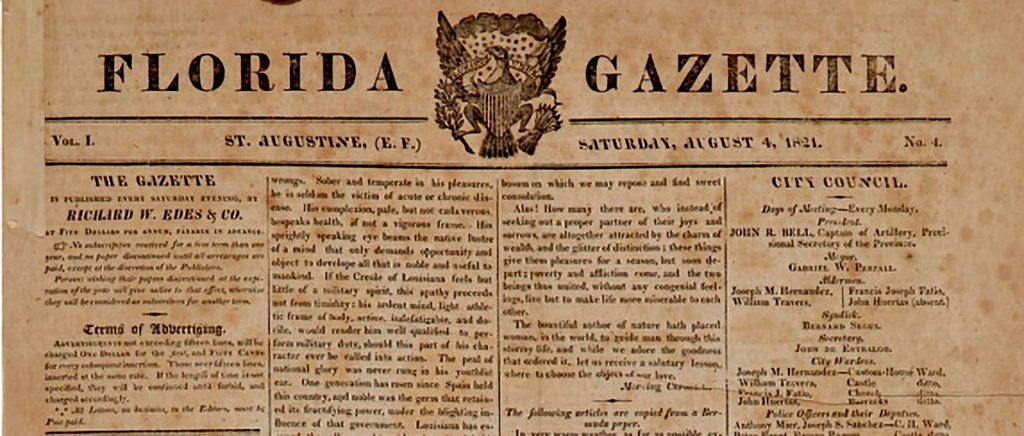

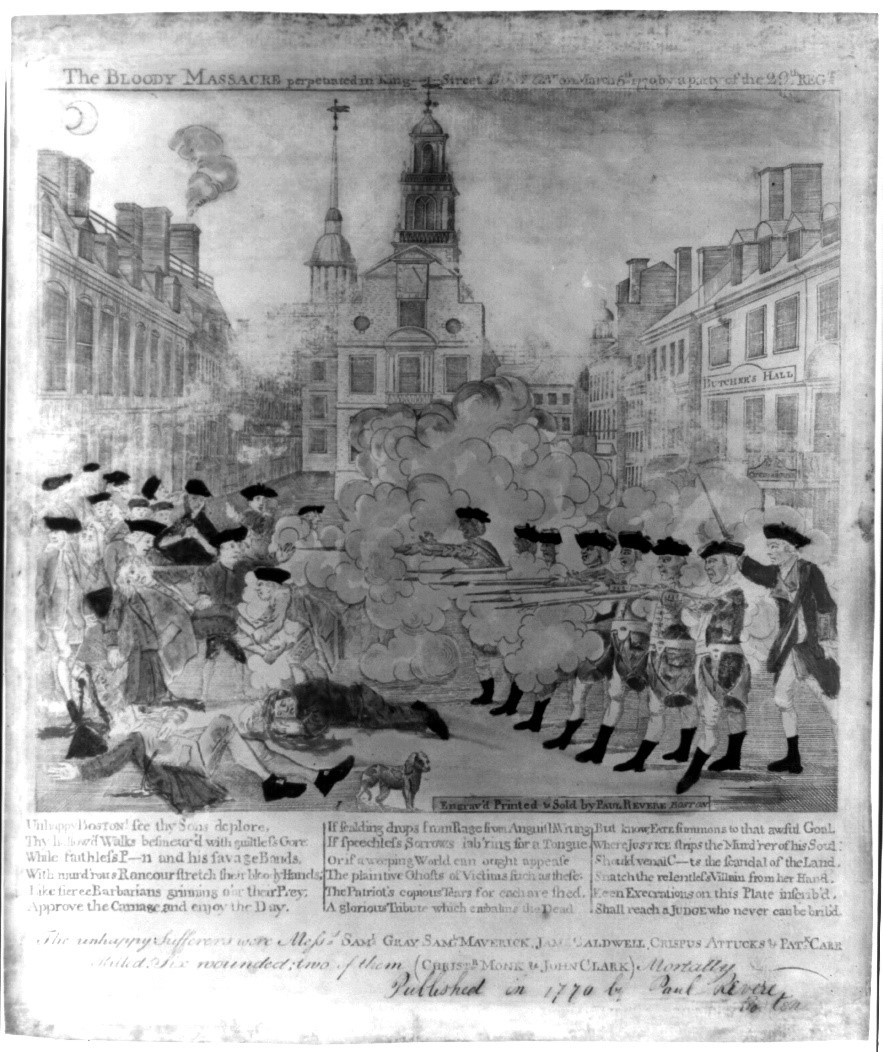

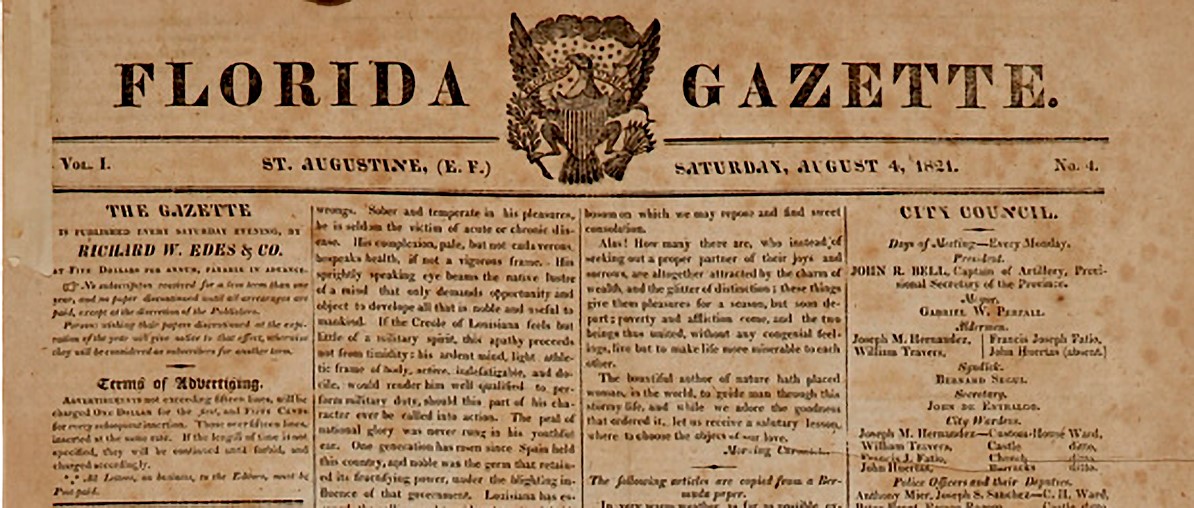

Benjamin Edes was born into a family of patriot printers: grandfather Benjamin Edes of Boston, father Peter Edes of Maine, and his younger brother, Richard W Edes, of Savannah and Saint Augustine. His grandfather, Benjamin Edes (1732-1803), was a revolutionary, a member of the Sons of Liberty, and earned the nickname “Trumpeter of Sedition.” His father, Peter Edes, was a pressman during the American Revolution who was imprisoned by the British for his activities. After the Revolution, he went on to publish a newspaper in Maine. His younger brother, Richard W. Edes, operated as a newspaperman in Savannah, Georgia, and later founded Florida’s first newspaper in Saint Augustine in 1821.

Benjamin Edes: Printer

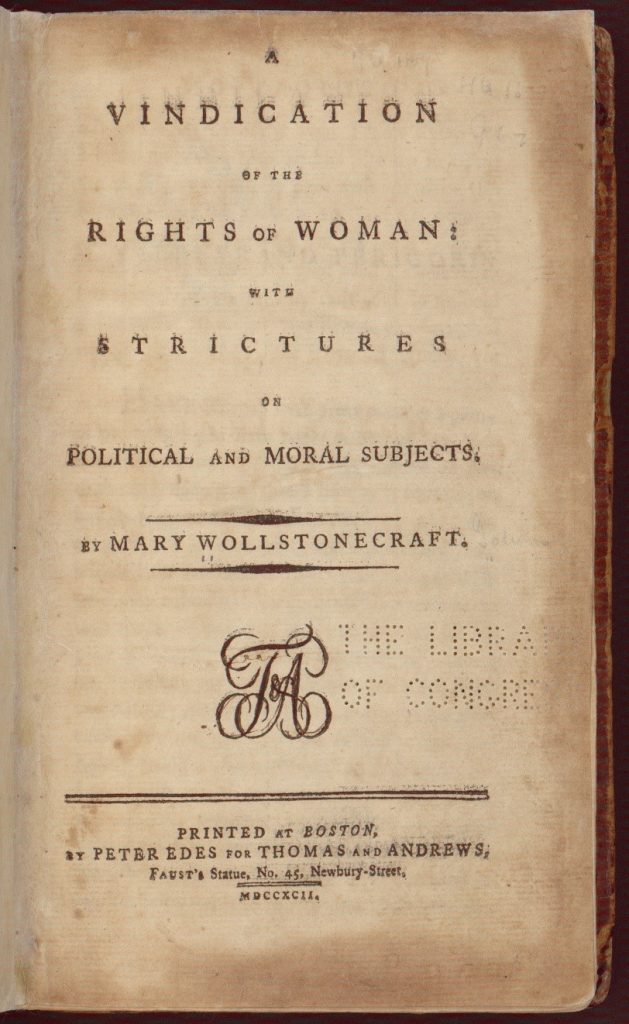

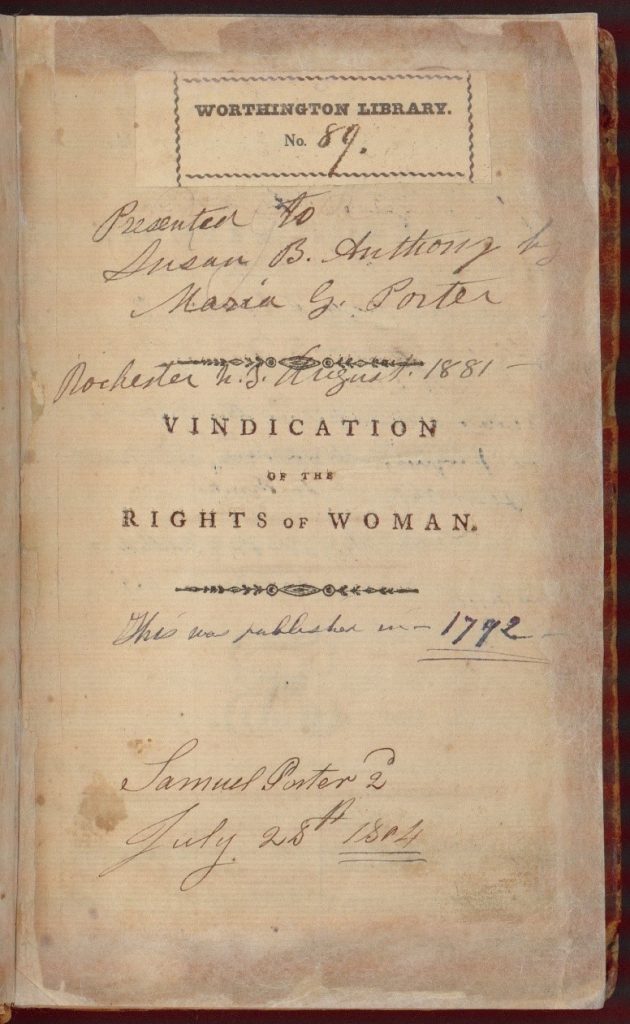

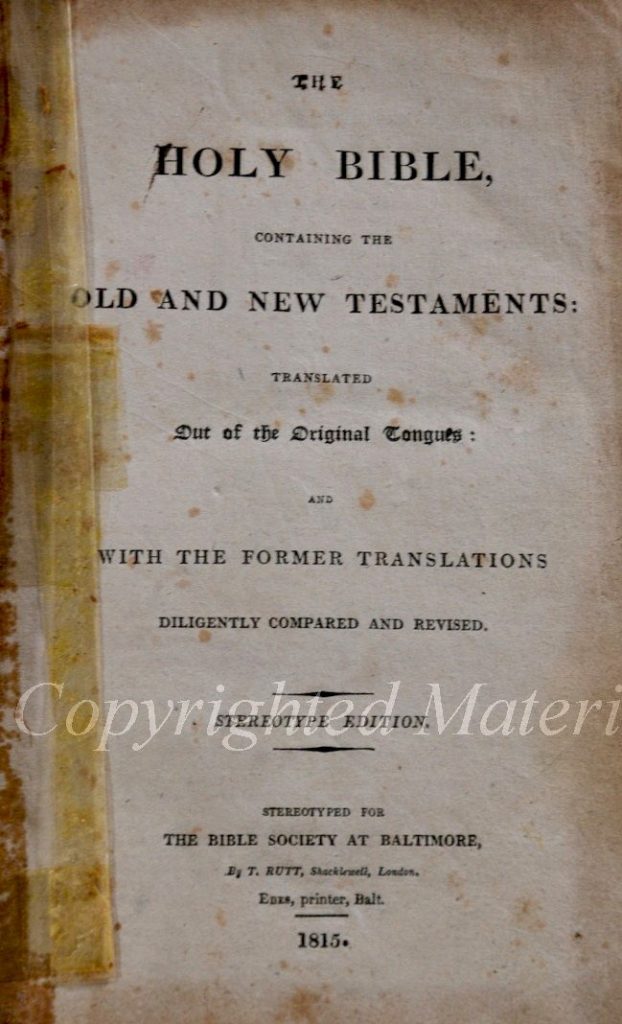

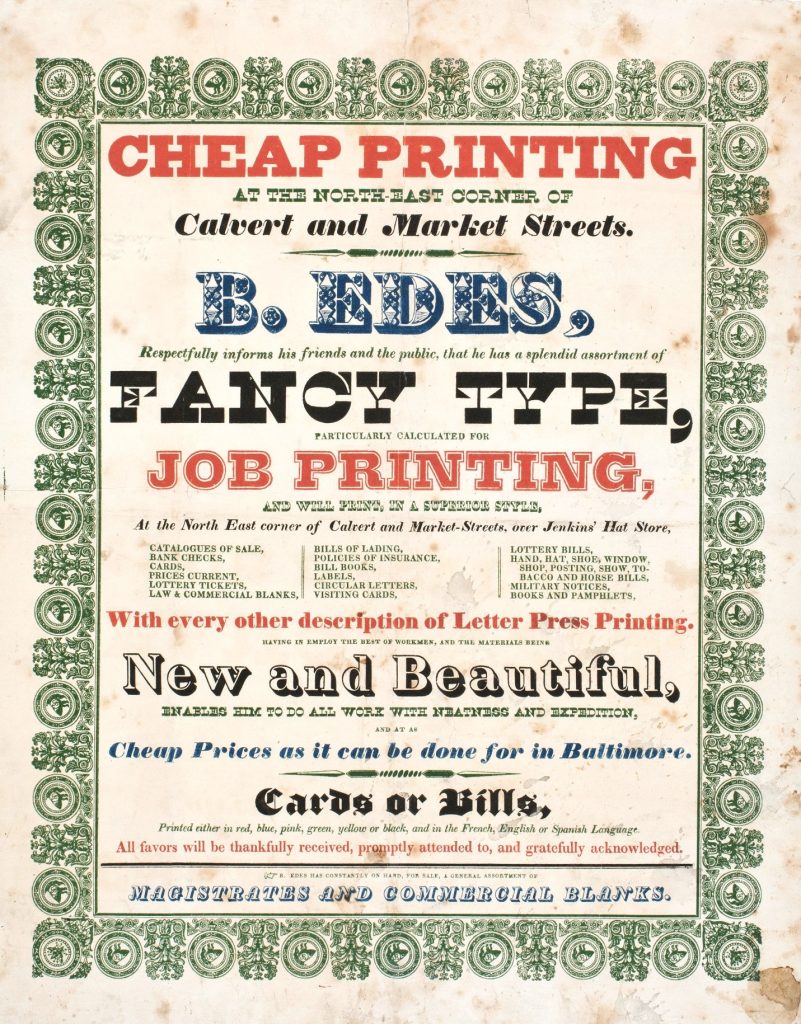

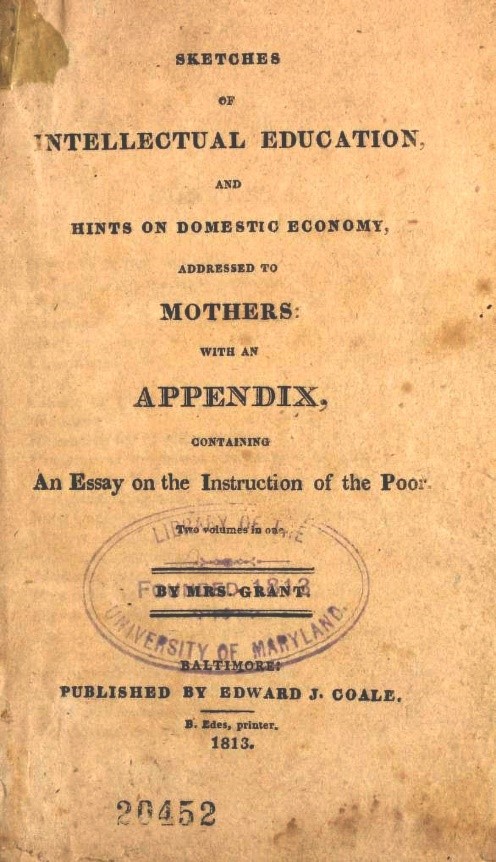

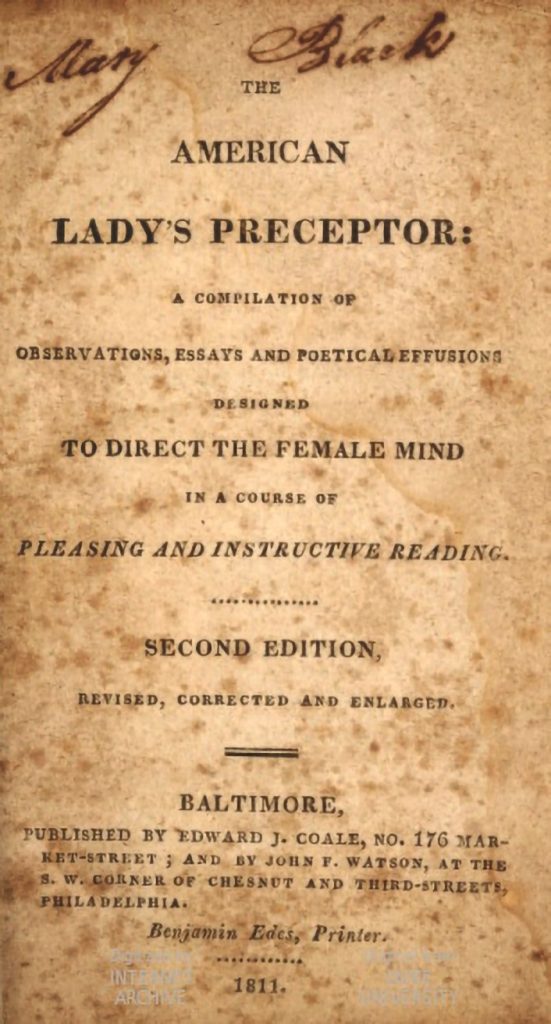

The first recorded evidence of Benjamin’s arrival in Baltimore is a document printed by the partnership Leakin & Edes. Shepard C. Leakin was a longtime resident of Baltimore who would go on to become its mayor. Edes, an experienced printer in New England, began his career in Baltimore through this partnership. Although the partnership would last only about a year, Edes remained a prominent printer in Baltimore from 1809 through his death due to cholera in 1832. In his time as a printer in Baltimore he was associated with the printing of Francis Scott Key’s Defence of Fort McHenry that later became known as the Star-Spangled Banner. He printed Baltimore’s first King James Bible using stereotype printing plate technology that was new in the U.S. at the time.

Benjamin Edes: Soldier

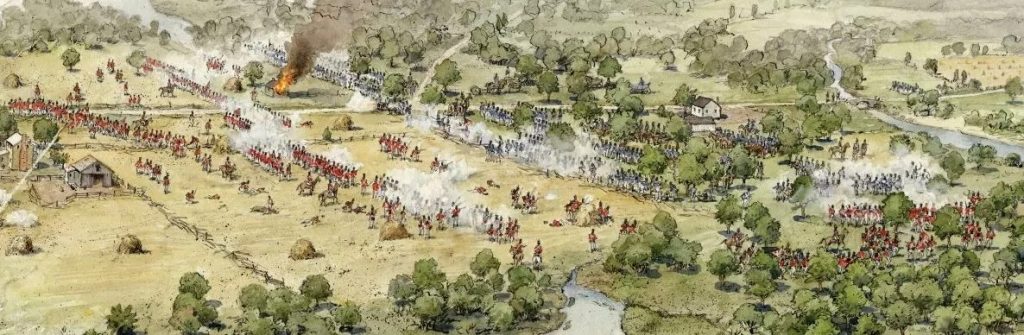

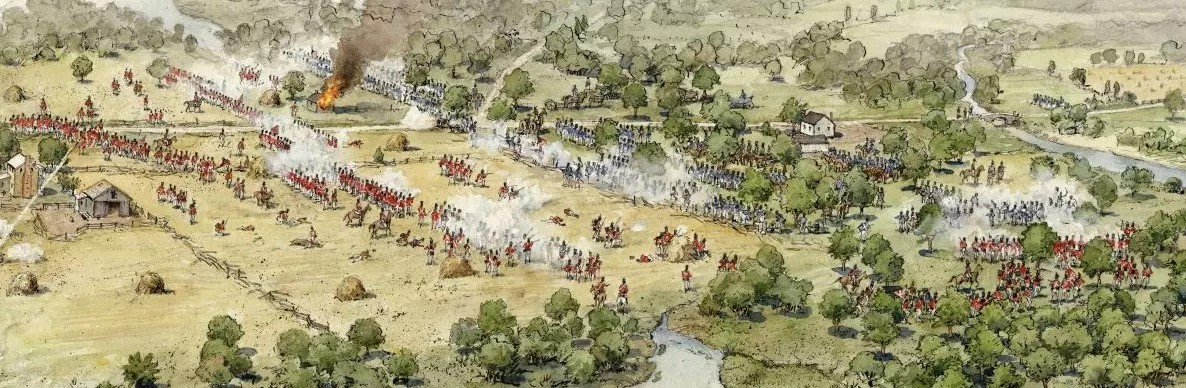

Given his family’s patriotic roots, it isn’t surprising that Benjamin Edes joined Maryland’s militia during the War of 1812. While his grandfather participated in the Boston Tea Party as a member of the Sons of Liberty during the American Revolution decades earlier, during the War of 1812 young Benjamin Edes served as an officer in Maryland’s 7th Infantry Regiment. A company commander, Ede’s fought on the frontline of that war when he commanded his unit during the Battle of Patapsco Neck, later known as the Battle of North Point in September 1814. There, he and his men faced the cream of Great Britain’s infantry, trained in combat by the Duke of Wellington. American forces caused many British casualties that day. When Edes died of cholera in 1832, he was a general in Maryland’s militia.

Benjamin Edes and Baltimore’s Printing Community (1805-1825)

The early 19th century marked a transformative period in American history, with Baltimore experiencing significant growth and cultural development. Among the many factors contributing to this growth was the emergence and flourishing of the printing industry. Printing played a key role in disseminating information, fostering intellectual conversations, and contributing to the practice of democracy. This exhibit explores printing in early 19th century Baltimore, highlighting its impact on education, communication, and the shaping of a vibrant civic society.

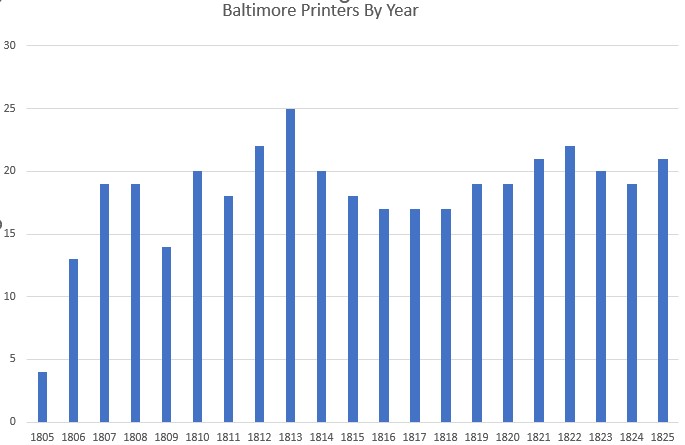

Between 1805-1825, evidence has been found of 120 printing entities operating in Baltimore. Approximately 50% of those printers only printed for a year or less. Another 30% operated for only two or three years, 95% six years or less. Only six printers of the 120 (5%) printed for seven years or more. We discovered evidence that Benjamin Edes printed for 17 years between 1805-1825. IStevenson University and Maryland Humanities: Printing in Baltimore Then and Now Project. Funded by the Council for Independent Colleges.)

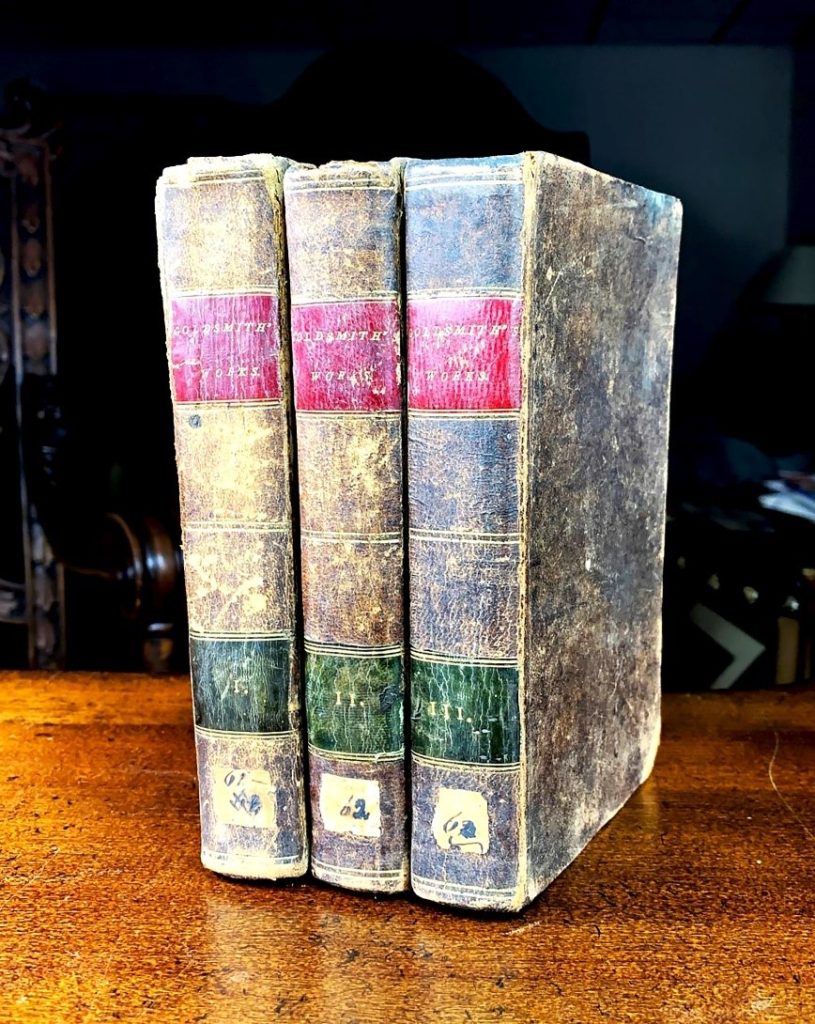

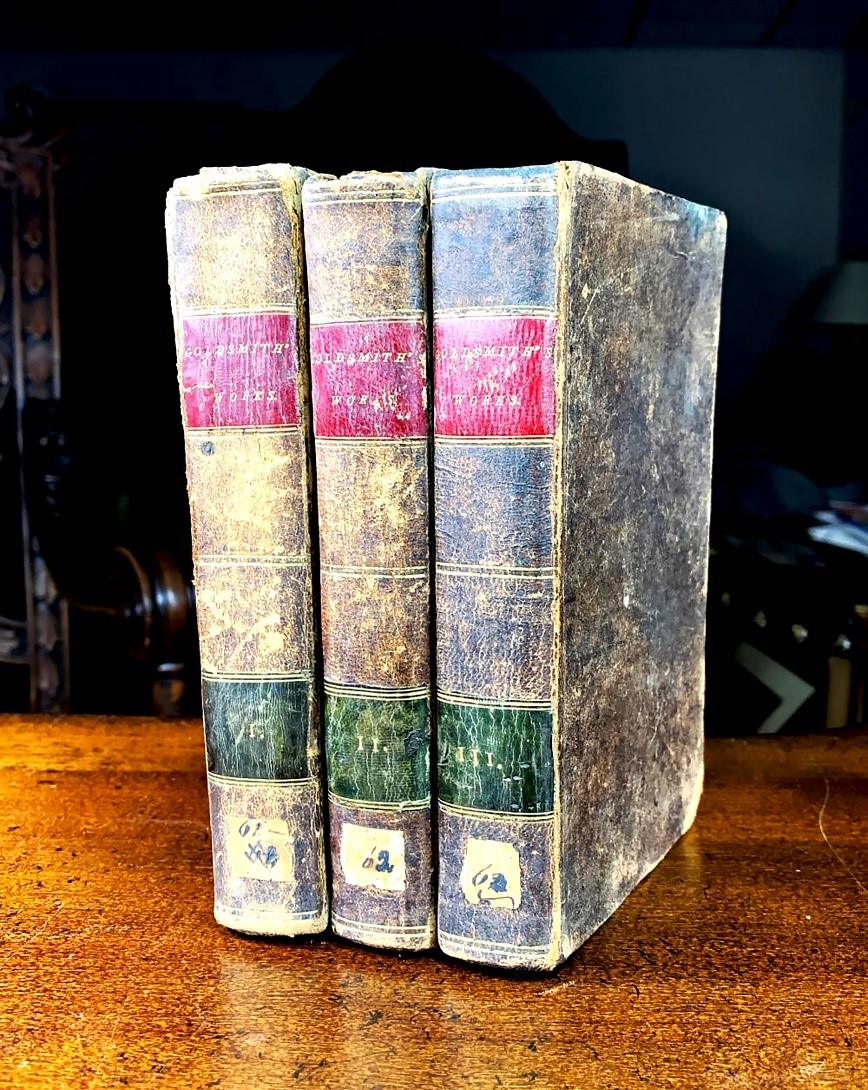

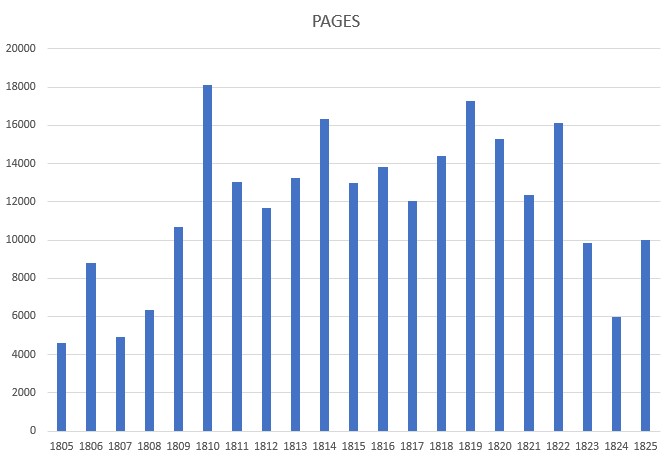

An imprint is a single printed document. An imprint can be a single-page broadside or it could be a three-volume collection of writings that runs 1300 pages in total length. You will notice that the number of imprints skyrockets in 1820. That is because a single printer, John Cole, who specialized in sheet music, published and printed over one hundred pieces of sheet music, each only one- or two-pages in length. IStevenson University and Maryland Humanities: Printing in Baltimore Then and Now Project. Funded by the Council for Independent Colleges.)

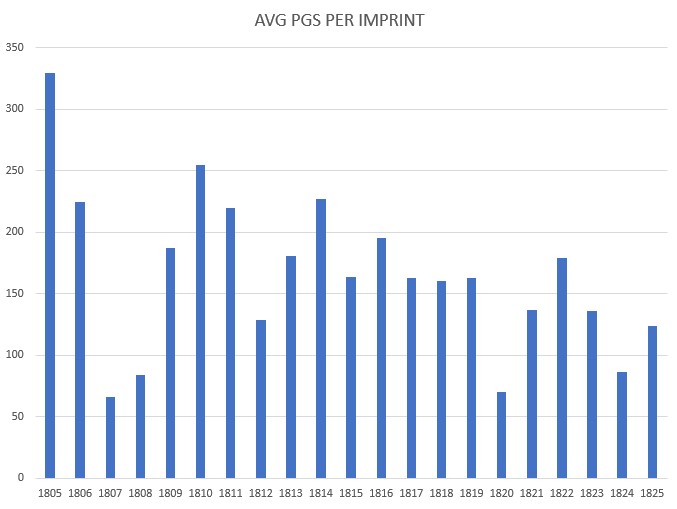

This spreadsheet provides information about the size or length of the average imprint in Baltimore per year. The lower the number, the shorter each imprint was, on average. With printers only being able to set one or two pages of type per day, multi-volume sets were generally beyond a single printer’s ability. Consequently, it was commonplace for several printers to join together and pool resources in order to produce imprints containing a large number of pages across multiple volumes. IStevenson University and Maryland Humanities: Printing in Baltimore Then and Now Project. Funded by the Council for Independent Colleges.)

This spreadsheet captures the productivity of Baltimore’s printing community by year between 1805-1825. IStevenson University and Maryland Humanities: Printing in Baltimore Then and Now Project. Funded by the Council for Independent Colleges.)

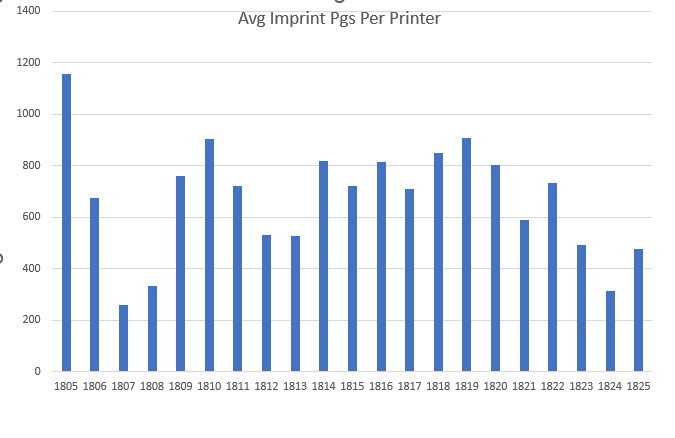

The average annual workload per printer is captured in this chart as measured by average pages printed per year. As can be seen, there were some very lean years for Baltimore’s printers. An interesting phenomenon is that while lean times are seen in 1812-1813, as one would expect as a result of America’s war with England (War of 1812), printing increased dramatically in 1814-1815 when Baltimore was directly attacked by the British or was recovering from that attack. The increase in printing is a result of the paperwork associated with coordinating Baltimore’s defense and recovery. IStevenson University and Maryland Humanities: Printing in Baltimore Then and Now Project. Funded by the Council for Independent Colleges.)

Printing and the Rise of Newspapers

In the early 19th century, Baltimore was witnessing a surge in population and economic activity. This created a fertile ground for the printing industry. The city became a hub for newspapers, which served as essential sources of information, entertainment, and opinion. Notable publications like the “Baltimore American” and the “Federal Gazette” thrived, providing opportunities for citizens to engage with local and national issues. These newspapers played a crucial role in shaping public opinion, fostering a sense of community, and laying the groundwork for an informed citizenry.

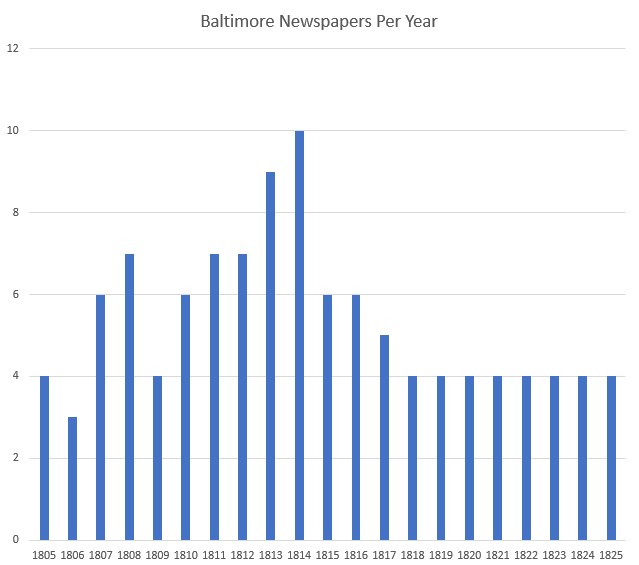

While the number of newspapers printed in Baltimore between 1805-1825 varied between three to ten, by 1818 that number of Baltimore newspapers had stabilized at four. IStevenson University and Maryland Humanities: Printing in Baltimore Then and Now Project. Funded by the Council for Independent Colleges.)

Educational Impact

Printing also played a vital role in advancing education in early Baltimore. The proliferation of printing presses enabled the production of texts, pamphlets, and other educational materials. As literacy rates rose, access to printed materials became increasingly democratic, contributing to the spread of knowledge and ideas across social class. The availability of affordable printed materials empowered individuals to engage with a wide range of subjects, from literature to science.

Printing and Baltimore’s Cultural Renaissance

Baltimore’s printing industry in Baltimore helped foster a cultural renaissance during the early 19th century. The publication of literary works, poetry, and essays contributed to Baltimore’s flourishing intellectual life. Writers, poets, politicians, religious figures, and business leaders found a platform through which they could share their ideas with a broader audience. Those 19th century “influencers” found a voice through local print media and shaped the cultural identity of the city.

The Loud Voice of the Press

Contrary to today, there were only two ways to communicate with the public. The first was to literally speak with them. The second was to communicate through the press. Of the two, the press had the greatest geographic reach, the greatest influence across class lines, and the greatest ease of access. Contrary to speeches, sermons, and conversations, printed materials could be read when the reader had the time.

Benjamin Edes, Baltimore, and the Humanities

The early 19th century marked a period of significant growth and transformation in Baltimore, a city that played a crucial role in shaping the intellectual and cultural landscape of the United States. Against the backdrop of economic expansion and social change, the humanities flourished, contributing to the city’s identity as a center of intellectual curiosity and cultural richness. This essay delves into the multifaceted aspects of the humanities in early 19th century Baltimore, exploring how literature, arts, education, and public discourse converged to create a vibrant and intellectually stimulating environment.

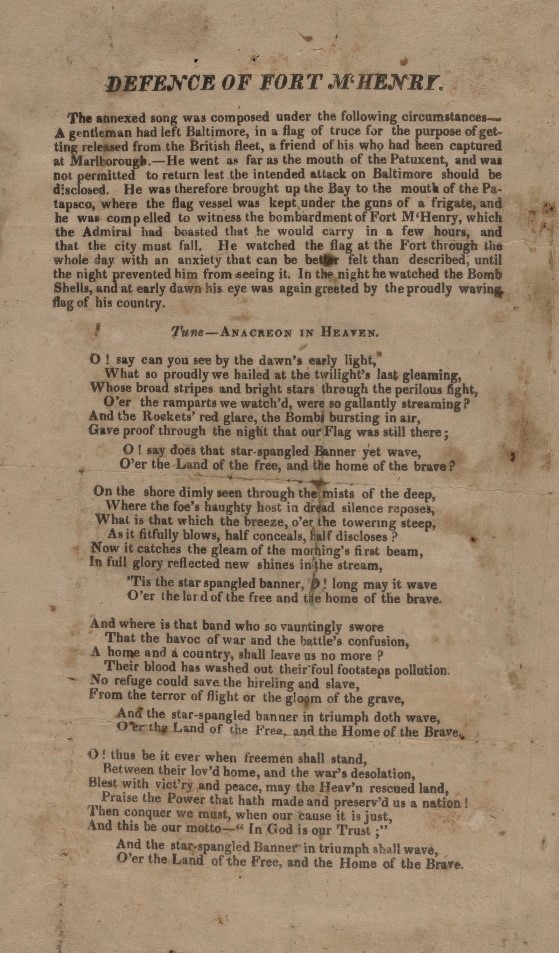

Benjamin Edes was still on the battlefield commanding his infantry company when Francis Scott Key’s father-in-law brought the lyrics to a song to be printed. Titled “Defence of Fort McHenry,” the lyrics were to be sung to the tune of Anacreon in Heaven. Edes’ apprentice, Samuel Sands, printed it as a handbill in Edes absence. The lyrics and that tune became our National Anthem. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

Baltimore’s Literary Renaissance

Baltimore’s literary scene in the early 19th century was characterized by a vibrant renaissance. The city became a hotbed for writers and poets, giving rise to a literary culture that would leave an indelible mark on American literature. Notable figures like Edgar Allan Poe, whose formative years were spent in Baltimore, contributed to the city’s literary legacy. Newspapers and literary journals provided platforms for local writers to share their works, fostering a sense of community and intellectual exchange.

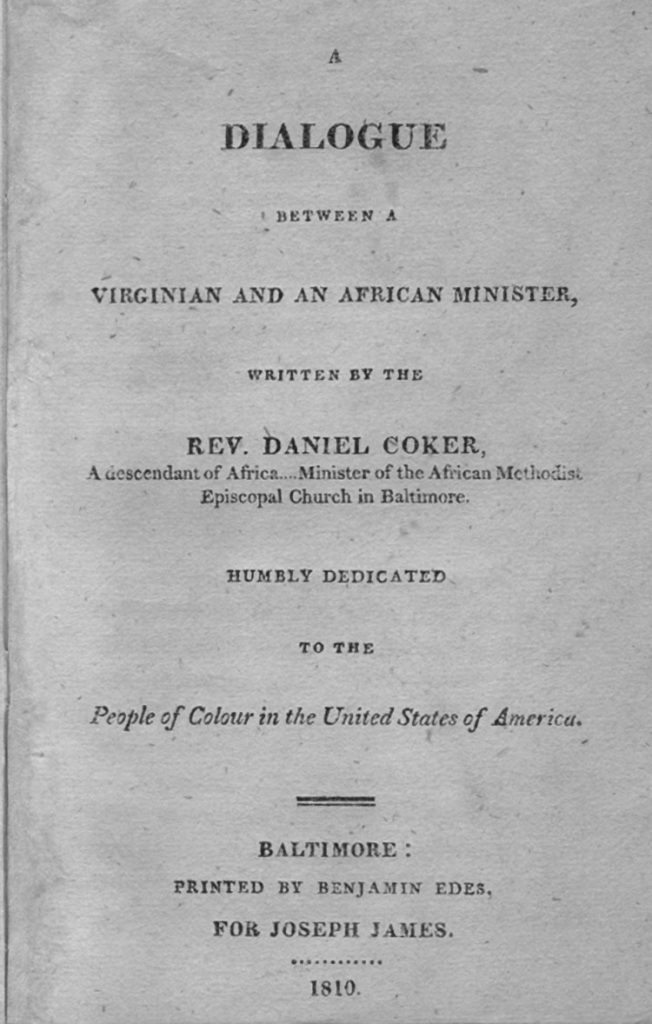

Born in Baltimore, Reverend Daniel Coker was an African American who wrote and preached the message of equality and abolition. A former slave, Coker was an advocate for the colonization of free African Americans to Africa, promoting the idea that this would provide them with greater opportunities and autonomy. By printing this book, Edes clearly identified his thoughts regarding equality. (Courtesy of Readex Early American Imprints. Series II, Shaw-Shoemaker (1801-1819))

Education and the Enlightenment

Education played a pivotal role in the intellectual development of early 19th century Baltimore. The city witnessed a growing emphasis on literacy and learning, with educational institutions emerging to meet the demands of a burgeoning population. The humanities, encompassing literature, philosophy, history, and the arts, became integral components of the curriculum. The Enlightenment ideals of reason, inquiry, and critical thinking permeated educational endeavors, shaping a generation of thinkers who would contribute to the broader intellectual currents of the time.

Cultural Institutions and Societies

Cultural institutions and societies emerged as focal points for the cultivation of the humanities in Baltimore. Literary and philosophical societies, such as the Mercantile Library Company, provided venues for intellectual exchange and debate. These organizations became crucibles for the exploration of ideas, with members engaging in discussions on literature, science, and philosophy. Such forums not only enriched the intellectual lives of Baltimore residents but also contributed to the city’s reputation as a center for enlightened thought.

One of the first subscription libraries in the United States, the Library Company in Baltimore focused on works thought to promote intellectual development. Printed by Edes & Leakin in 1809, this was one of Benjamin Edes’ first projects in Baltimore. (Courtesy of Google Books)

Visual and Performing Arts

The humanities in early 19th century Baltimore extended beyond the written word, encompassing the visual and performing arts. The city’s cultural landscape saw the emergence of theaters, art galleries, and musical venues. These spaces became platforms for artistic expression, where painters, actors, and musicians showcased their talents. The convergence of various artistic forms contributed to the creation of a rich and diverse cultural tapestry that reflected the city’s dynamic and cosmopolitan character.

Public Discourse and Civic Engagement

Printed newspapers and public discourse played a crucial role in disseminating humanities-related ideas to a broader audience. Newspapers, such as the “Baltimore American” and the “Federal Gazette,” served not only as sources of information but also as forums for the exchange of ideas on literature, philosophy, and societal issues. Public lectures and debates further fueled intellectual engagement, fostering a sense of civic responsibility and participation in the cultural and intellectual life of the city.

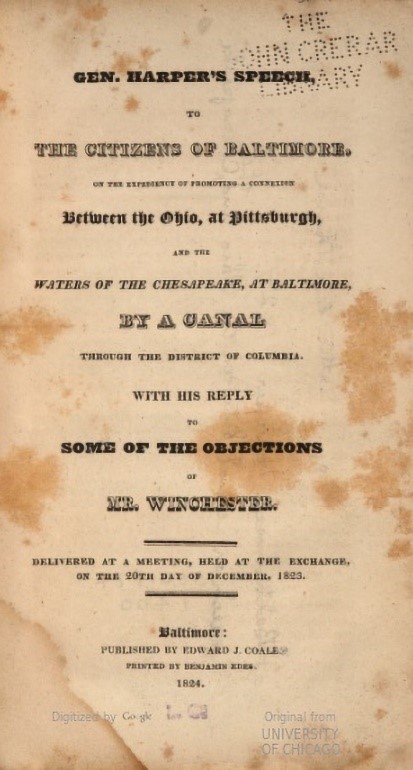

General Harpers’ Speech to the Citizens of Baltimore is an example of how the press served as the social media of its day. Printed by Edes in 1824, this document carried forth the discussion of a canal from Baltimore to Pittsburgh but, in a much larger sense, the discussion of the central government’s role in internal improvements. (Courtesy of the Internet Archive)

Letterpress Printing in 21st Century Baltimore

In an age dominated by digital technologies, the art of letterpress printing has experienced a remarkable renaissance in the 21st century. Originally a cornerstone of the printing industry for centuries, letterpress, with its tactile beauty and historical significance, has found a renewed appreciation among artists, designers, and enthusiasts. This essay explores the revival of letterpress printing in the 21st century, examining its enduring appeal, technological adaptations, and its role in contemporary artistic and commercial contexts.

As we began our expedition into Baltimore’s 21st century press community, Kari Miller, owner and operator of Tiny Dog Press, was our guide and our muse. An experienced craftsperson, Kari is an excellent teacher, making the time fly by. (Photo by Micah Coate, courtesy of Tiny Dog Press, Baltimore)

Historical Roots and Artistic Heritage

Letterpress printing, characterized by the relief technique of pressing inked movable type or blocks onto paper, has a storied history dating back to Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press in the 15th century. In the 21st century, its revival is rooted in a desire to reconnect with traditional craftsmanship and the tangible qualities of printed material. Artisans and printmakers are drawn to the historical roots and artisanal charm of letterpress, valuing the tactile experience it offers in an era dominated by mass-produced digital prints.

The Tiny Dog Press is proud of the Chandler & Price platen press that does much of their work. It was this form of press that ushered manual printing into the 20th century and was the mainstay of many a printshop from the 1880s through the 1930s. (Photo by Ana – Side A Photography. Courtesy Tiny Dog Press of Baltimore)

Craftsmanship in the Digital Age

In a world saturated with digital images and automated printing processes, letterpress printing stands out as a testament to craftsmanship and manual dexterity. The slow, deliberate process of setting type, inking the press, and hand-feeding each sheet of paper contributes to the creation of unique, tangible artifacts. The resurgence of interest in letterpress reflects a cultural shift towards valuing the authenticity, imperfections, and individuality inherent in handcrafted objects.

And here is where it all comes together. Printing a piece of art. (Photo by Ana – Side A Photography. Courtesy Tiny Dog Press of Baltimore)

Artistic Expression and Personalization

The 21st-century letterpress revival is marked by a fusion of tradition and contemporary artistic expression. Artists and designers embrace letterpress as a medium that allows for experimentation and creativity. The process lends itself to the creation of bespoke, personalized pieces that carry a distinctive aesthetic. Wedding invitations, business cards, and art prints crafted through letterpress printing become not just functional items but also tangible expressions of individuality and artistic intent.

Adaptation to Modern Technologies

While rooted in tradition, letterpress printing in the 21st century has not shied away from embracing modern technologies to enhance efficiency and expand creative possibilities. Designers often utilize digital tools for type design and layout, seamlessly integrating them into the letterpress process. This marriage of traditional craftsmanship with contemporary design tools enables artists to push the boundaries of what is achievable while preserving the essential characteristics of letterpress printing.

Community and Education

The resurgence of letterpress printing is not just about producing beautiful prints; it is also about building communities and passing on traditional skills. Printmaking studios and workshops have become hubs for enthusiasts and novices alike, fostering a sense of community and shared appreciation for the craft. Educational programs and institutions offer courses on letterpress printing, ensuring that the knowledge and techniques are preserved and passed on to future generations.

The Humanities in 21st Century Baltimore

The study and appreciation of the humanities have undergone profound transformations over the centuries, shaped by societal, technological, and cultural shifts. A particularly intriguing comparison lies between how individuals engaged with the humanities in the early 1800s and how they access these disciplines today. This essay explores the key differences in the modes of engagement, sources of information, and societal contexts that distinguish these two periods.

The flagship institution in Maryland representing the humanities is Maryland Humanities. Their mission is to create and support bold experiences that explore and elevate our shared stories to connect people, enhance lives, and enrich communities. They teamed with Stevenson University on this project as a way to research a deeper understanding of the humanities through Maryland’s history. (Logo courtesy of Maryland Humanities)

Accessibility and Dissemination of Knowledge

In the early 1800s, access to the humanities was largely restricted to the privileged few. Wealthy elites and scholars had the means to acquire books, attend lectures, and participate in literary societies. The dissemination of knowledge was often confined to formal education settings and exclusive literary circles. Libraries were limited, and books were precious commodities.

Contrastingly, today’s access to the humanities is characterized by unprecedented democratization. The advent of the internet has revolutionized the dissemination of information, making a vast array of literary works, artworks, and educational resources accessible to people worldwide. Digital libraries, online courses, and open-access platforms have dismantled many barriers to entry, allowing individuals from diverse backgrounds to engage with the humanities at their own pace and on their own terms.

Within the City of Baltimore, the single biggest venue for people to access the humanities is through the Enoch Pratt Free Library and its collections and programs. As technologies have changed, the Enoch Pratt has not only kept pace, it has often been on the leading edge of the public’s needs. (Logo courtesy of the Enoch Pratt free Library.)

This graphic from the Enoch Pratt free Library 2023 annual report graphically exhibits how the people of Baltimore interact with information today. It is p\undoubtedly the single best illustration of how the humanities are consumed today by Baltimore’s residents. (Courtesy of the Enoch Pratt free Library).

Technology and Cultural Consumption

In the early 1800s, engaging with the humanities was a predominantly analog experience. Books, handwritten manuscripts, and printed materials were the primary mediums. The emergence of newspapers and literary journals expanded access, but the overall pace of cultural consumption was slower. The physical act of reading, attending lectures, or participating in discussions constituted the main avenues for intellectual and artistic engagement.

In the contemporary era, technology has transformed the landscape of cultural consumption. Digital platforms offer a plethora of multimedia experiences, including e-books, audiobooks, podcasts, online courses, virtual art exhibitions, and streaming services for films and performances. The integration of technology has not only broadened the spectrum of available content but has also accelerated the pace at which individuals can engage with the humanities.

PBS is a member sponsored organization that, in partnership with its member stations, serves the American public with programming and services of the highest quality, using media to educate, inspire, entertain and express a diversity of perspectives. PBS empowers individuals to achieve their potential and strengthen the social, democratic, and cultural health of the U.S. PBS offers programming that expands the minds of children, documentaries that open up new worlds, non-commercialized news programs that keep citizens informed on world events and cultures and programs that expose America to the worlds of music, theater, dance and art. It is a multi-platform media organization that serves Americans through television, mobile and connected devices, the web, in the classroom, and more. (Logo courtesy of PBS)

YouTube’s self-stated mission is to give everyone a voice and show them the world. YouTube believes that everyone deserves to have a voice, and that the world is a better place when we listen, share and build community through our stories. While YouTube was not designed to further the mission of the humanities, it does so, for free, on a daily basis through its lectures, events, and movies. (Logo courtesy of YouTube)

Educational Paradigms

In the early 1800s, formal education was often reserved for the elite, emphasizing classical studies in the humanities. The curriculum was structured, and educational institutions played a central role in shaping intellectual development. Students engaged with the humanities through traditional pedagogical methods, including lectures, discussions, and close textual analysis.

Today’s educational paradigms in the humanities reflect a more diverse and inclusive approach. Formal education is widely accessible, with a focus on interdisciplinary studies, critical thinking, and experiential learning. Online courses, distance education, and digital resources enable individuals to pursue humanities education beyond the confines of physical classrooms, fostering a more flexible and personalized approach to learning.

Social and Cultural Context

The social and cultural context of engaging with the humanities in the early 1800s was deeply influenced by the values and norms of the time. Societal hierarchies and class distinctions played a role in shaping who had access to intellectual and artistic pursuits. The cultural milieu was characterized by a blending of Enlightenment ideals, classical influences, and emerging national identities.

In contrast, the present-day context is marked by greater diversity, globalization, and an increased awareness of social justice issues. The humanities are seen as crucial in addressing contemporary challenges, fostering empathy, and promoting cultural understanding. Modern engagement with the humanities is influenced by a more inclusive worldview that values diverse perspectives, voices, and narratives.

SU CIC Project Conclusions and Acknowledgements

Conclusions

This study began with one central research question: What was the relationship between the press and the humanities in the early 19th century and today? We choose convenience samples from each era. The print shop of Baltimore’s Benjamin Edes represented printing in the early 1800s. Baltimore’s Tiny Dog Press represents small press printing today. We engaged in extensive research that provided a context for those case studies. Having engaged in research for one year, the following assertions are supported by evidence we uncovered in our investigation.

1. The humanities are strong, but the means of access have changed dramatically between the early 19th century and today.

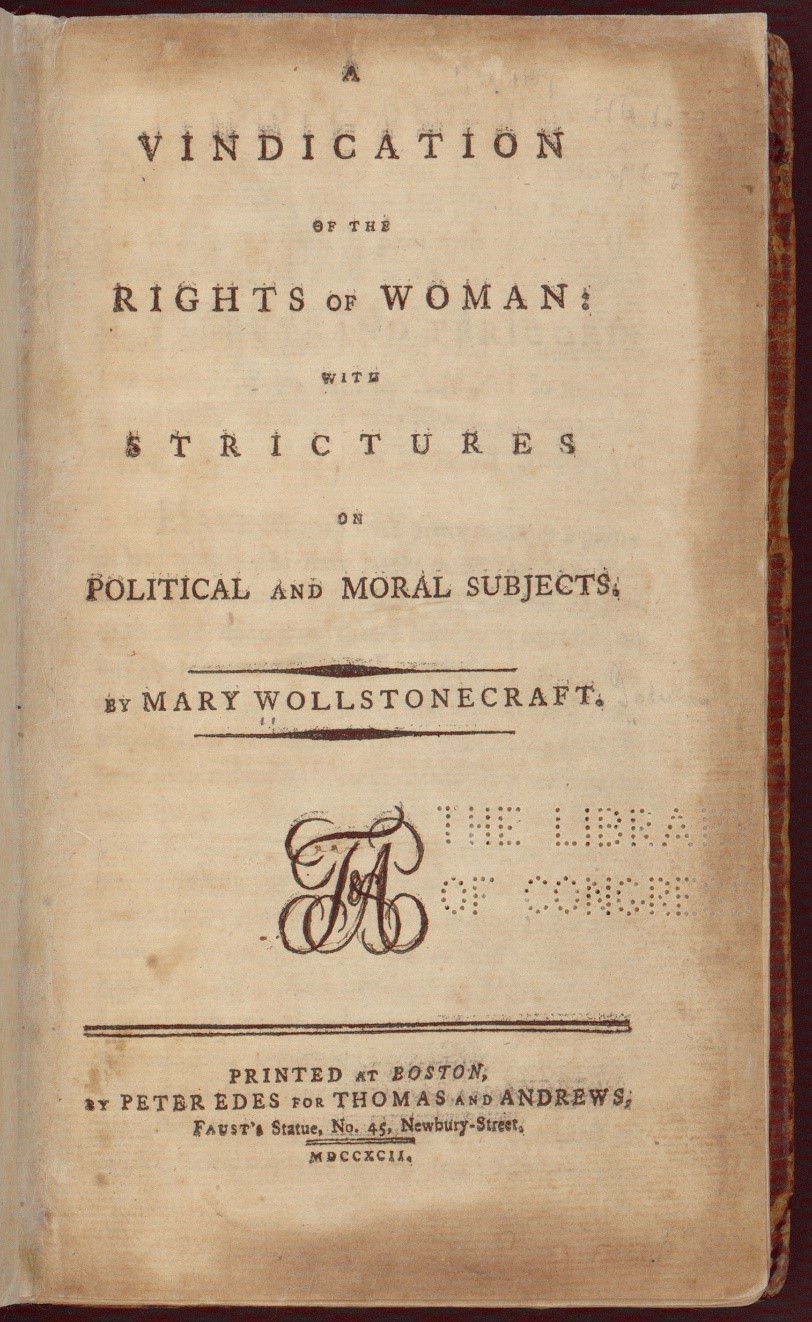

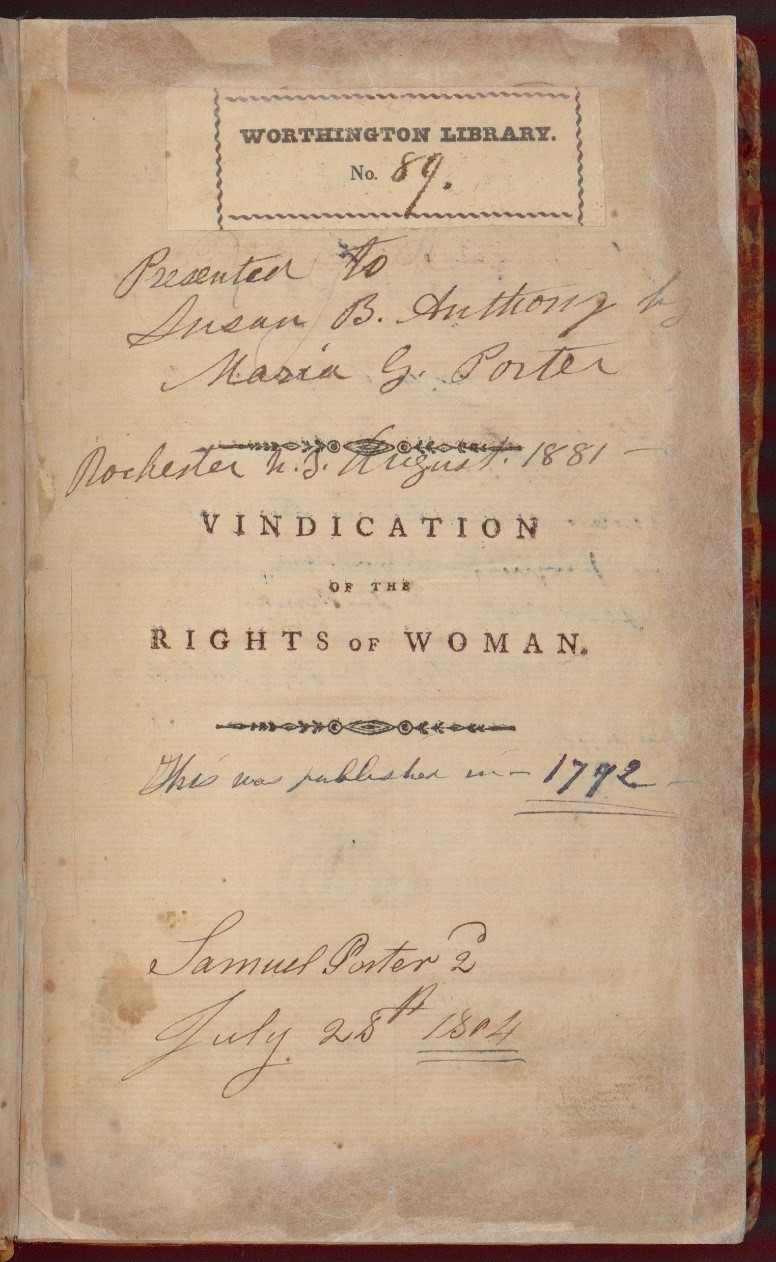

In the early 1800s, people engaged with the humanities in only two ways: in person or virtually. Local events and live performances provided venues for engaging with the humanities in person. Virtual engagement with the humanities was through printed media. To serve that need, Baltimore’s printers provided a steady diet of books, monographs, essays, epic poems, lyrics, songs, sermons, and speeches, as well as collections of maps, illustrations, and fine art. A large percentage of Baltimore’s imprints from the early 1800s consisted of US editions of European classics that were, and still are, iconic examples of the humanities. However, a barrier to virtual engagement in Baltimore in the early 19th century existed: illiteracy. Without a public education system, with an economy that did just fine with a workforce whose literacy extended only to that required by their occupations, and with laws that discriminated against Black people trying to gain an education, a large part of the public could not enjoy the humanities virtually because they couldn’t read. Hence the popularity of public performances.

In the 21st century, that same basic relationship between the humanities and public access to the humanities still exists: the public can enjoy the humanities in person at an event or a performance, or they can enjoy the humanities virtually. The most significant change, and a change that has dramatically affected small presses, is the ability of the public to virtually engage with the humanities in ways other than through print. First, through photography, radio, movies, and subsequently through television and digital streaming, the public can access the humanities as virtual “live” performances through an amazing array of electronic options. Although print media are still an essential way for the public to virtually engage with the humanities, print is no longer king. Instead, digital means of delivery surpass all others.

2. While reading literacy was important when virtually accessing the humanities in the early 19th century, increasingly, it is technical literacy in the digital humanities that matters today.

In the early 19th century, if you wanted to experience the humanities virtually, you had to be able to read. That isn’t true in the 21st century. According to the National Center for Educational Statistics (2022), only 15% of Baltimore’s students can read to the grade-level proficiency required by the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). That agency also reports that 20% of Maryland’s population is functionally illiterate. That should have been the death knell for the humanities. However, access through media other than print has provided widespread access to the humanities through television, streaming services, movies, podcasts, and audiobooks. That being said, digital access requires its own literacy.

There is one area of the humanities that remains strong in its print form. That area is fiction. Popular trade books that serve the public’s need for light reading and entertainment are still an important segment of the print industry worldwide. According to Statista.com (2024), while audiobook sales have doubled since 2011, they are only 23% of total book sales. People prefer to read novels in hard copy.

3. The world of letterpress printing in Baltimore has changed dramatically since the early 19th century. The changes have largely been in the factors motivating the printer and the outcomes experienced by the printer and their clients.

Printers in the early 19th century operated their presses as a vocation, and their material well-being was primarily determined by the output of their presses. Job printers, those who relied on letterheads, invoices, handbills, lottery tickets, and other miscellaneous work to buoy sales when not occupied with printing books and periodicals, were the rule rather than the exception. Printers in early 19th century Baltimore were primarily motivated by income and by exercising their rights under the 1st Amendment of the Constitution, advocating on behalf of a political party or a political leaning.

An example of this was Baltimore’s Federal Republican riots of 1812. In the politically charged atmosphere at the start of the War of 1812, Alexander Contee Hanson’s Federal Republican & Commercial Gazette, printed in Baltimore, supported the Federalists and maintained an anti-war stance. This was an explosive position since Baltimore was largely Democratic Republican and supported the war. In the summer of 1812, things came to a head. Weeks of rioting took place. Over a period of weeks, Hanson’s print shop was repeatedly attacked, people killed, and his print shop destroyed. It took the presence of the Maryland Militia to quell the riots.

Consumers of the output of Baltimore’s small presses in the early 19th century were most interested in the information on the printed page. Aesthetics took a rear seat to the display of information. While symbols in newspapers were widespread, they were not used for their artistic content. Instead, they were used to identify a category of advertisements for the reader. For example, a silhouette figure of a young Black man walking with a bindle was often used for advertisements seeking the return of an escaped enslaved person or indentured servant. The image of a three-masted ship under full sail often marked columns containing what was known as “marine intelligence,” the arrival and departure of ships from port. Books were purchased for the text they contained, and handbills read for their late-breaking news or announcements of public events.

In contrast to those printers of the early 19th century, many letterpress printers in the early 21st century engage in letterpress printing as a hobby. They enjoy how the printing experience engages them physically and at a sensory level. They enjoy the effort they put into creating a functional and aesthetically appealing product. Their products are often high-end stationary, invitations, programs, print advertising, calendars, and pamphlets. In each instance, their products contain information, but their products also look and a feel unlike similar products produced by a commercial press. Their clients appreciate the richness of their products and their feel, the way the print is actually pressed into the paper. Letterpress printing provides a product with a three-dimensional feel to the touch. For products designed to emulate similar documents from the 18th and 19th centuries, clients enjoy a four-dimensional experience, with the fourth dimension being time.

Acknowledgments

We would like to take this opportunity to thank those who helped us in our study from outside Stevenson University. They include:

- Kari Miller, Tiny Dog Press

- Edward C. Papenfuse, Maryland State Archivist and Commissioner of Land Grants ( Ret.)

- Scott Sheads, National Park Service Historian (Ret.)

- Ranger Tim Ertl, Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine, National Park Service

- David H. Moore, former Superintendent, Fort McHenry, National Park Service

- Stephen G. Heaver. Proprietor, Hill Press

- Michael B. Tager, Managing Editor, Mason Jar Press

- Philip M. Katz, Senior Director of Projects, Council of Independent Colleges

- Aditya Desai, Program Officer, Literature, Maryland Humanities

- Eden Etzel, Program Assistant, Maryland Center for the Book, Maryland Humanities