Stevenson’s history students are learning about Civil War medicine and surgery by examining the experiences of Marylanders who were killed, wounded, or missing during the Battle of Antietam in September 1862. Along the way, those students are creating a one-of-a-kind database that examines those experiences through the records and writings of the soldiers themselves.

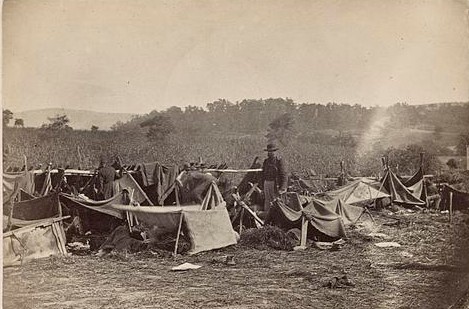

CAPTION: Union Military Surgeon Dr Anson Hurd stands amidst rough shelters in farm field for wounded Confedferate soldiers. (Courtesy Library of Congress)

As the students prepared for their research they attended lectures, were guided through multiple videos, analyzed photographs taken on that battlefield just hours after the battle had ended, and studied best practices of military surgeons from the Revolutionary War through the Crimean War. Once acquainted with state-of-the-art medical techniques, pharmaceuticals, instruments, and procedures at the beginning of the Civil War it was time to begin the major task of the course. Each student received between two to four names of men who were wounded, killed, or recorded missing as a result of the battle. All of the initial information came from one source: the History and Roster of Maryland Volunteers, War of 1861 – 1865. Published more than 30 years after the war had ended, in 1898-1899, the report was published in Baltimore by Guggenheimer, Weil & Co. in two volumes. Running a little over 1,100 pages in length, the two volume set is the product of a massive undertaking. It was chosen as the guiding text for the class because so much of its information is wrong.

CAPTION: Drawings of round and conoidal bullets extracted from wounds of Union soldiers. (Courtesy of Medical & Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, US Army)

As the history students began researching each of the men they were assigned, they soon learned that they couldn’t trust any one source. Their research into one person across multiple sources of information often raised more questions than it answered. Looking through their soldiers’ compiled service records, widows’ pension files, veterans schedules of the 1890 US Census, National Soldiers Homes records, court-martial proceedings, prisoner-of-war documents, hospital records, and newspaper accounts, Stevenson’s undergraduate researchers soon uncovered misspelled names, aliases, incorrect unit assignments, wounds and deaths from the Second Battle of Bull Run on August 29th 1862 that were identified as having happened at Antietam, and disagreements between sources regarding the wounds themselves as well as battlefield deaths. Contrary to how history is traditionally taught, students in this class got to see history as it actually is found in primary sources: messy. Their first job was to sort out a storyline that best fit the facts as they pertained to each of their soldiers. Once each narrative was developed in a bare bones fashion, the students had to breathe life into those bones.

CAPTION: Union soldiers (Zouaves) practice loading Army ambulance. ( Civil war photographs, 1861-1865, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division. )

In order to humanize historical evidence from the past, student researchers had to apply what they had learned in an unemotional, academic setting to the actual experiences of the real soldiers they were studying. Who were these men? Where had they come from? What must their lives have been like prior to the war? Who were their families? What were their occupations? How did the war affect their lives? What medical treatment would have been undertaken to help them after they were wounded and what were the limitations of that treatment? What were the characteristics of the weapons that wounded or killed them and what were the terminal ballistics of the projectiles that hit them? How would they have been found after they were wounded? Who would have provided aid? Where would they need to go for medical help and how far away was that? These questions and dozens more helped the students gain an appreciation for what the soldiers had endured.

CAPTION: Army officers and medical men surround Civil War military surgeon demonstrating amputation technique. (Courtesy of National Museum of Medicine, NIH)

Along the way the student researchers stumbled onto story lines that were as compelling as they were colorful. The officer from a Maryland regiment charged with cowardice, court-martialed, and found not guilty by the officers of the court only to have that decision reversed by President Lincoln himself. The infantry company from Maryland’s 5th Regiment that was advancing toward the enemy with the rest of the regiment until they found themselves stopped by a farmer’s fence. Once through the fence their formation was broken up by angry hogs who knocked the men down like bowling pins. The remainder of the regiment was still moving ahead but this particular company had stopped and was in chaos on the battlefield. As the men were running away from the hogs a Confederate artillery round hit several nearby bee hives. The mayhem that ensued as the men tried to escape both the hogs and the bees prevented that company from advancing with the other companies of the 5th. On that fateful day at Antietam, the day the 5th Maryland fought so hard and lost so many men at the Battle of the Sunken Road, sometimes called Bloody Lane, the regiment was short one company on the battle line. When the missing company was finally able to clear its problems at the farm and reorganize to advance to the battle it arrived too late. Not one man from that company was wounded or killed that fateful day of 17 September 1862.

CAPTION: Portrait photo of Dr Jonathan Letterman, Chief Medical Officer, Army of the Potomac at the Battle of Antietam. Innovations he introduced revolutionized the care of wounded soldiers and influence most major armies even today. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

The kind of hands-on learning described above provides insight into the past unlike other forms of learning. Classroom learning sets the stage and provides context for what students uncover in their research and leads to empathy for the experiences of people in the past. Classroom teaching allows students to hold a .58 caliber bullet in their hands and to see in super slow motion what that bullet can do as it enters a block of ballistic gel and destroys embedded bone and muscle. Learning in class that Civil War medicine was unfamiliar with germ theory, students can understand the hidden implications of casualty reports one sentence in length. Reading a short description of a soldier’s wound: “Gunshot wound to abdomen by conoidal bullet,” the student now knows why that soldier would most probably die of that wound and what kind of lingering, painful death it would be. Context development through classroom instruction enables students to understand the implications of the material uncovered in their own research. They can now empathize with the fact that the soldier would know he was going to die, the doctors would know that, and little could be done to stop infection. The surgeons wouldn’t operate since to do so would dramatically increase the chance of infection. Short of God’s intervention, there was nothing to prevent the pain and suffering associated with a death like this.

CAPTION: Nurse caring for wounded after the Battle of Antietam at Smoketown Hospital. (Courtesy of National Museum of Medicine, NIH)

History, as one of the Humanities, has at its foundation understanding the human experience. Facts devoid of human understanding are simply that, facts. When accompanied by human understanding, empathy, and the desire to experience the past through the eyes of others, facts can become the building blocks of stories that are both compelling and informative. The kind of stories that make good history.